Consider Exercise 2 Again. Assume That the Firms Form a Cartel

Chapter 10. Monopolistic Competition and Oligopoly

10.2 Oligopoly

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, y'all will exist able to:

- Explain why and how oligopolies exist

- Contrast bunco and competition

- Translate and analyze the prisoner's dilemma diagram

- Evaluate the tradeoffs of imperfect competition

Many purchases that individuals make at the retail level are produced in markets that are neither perfectly competitive, monopolies, nor monopolistically competitive. Rather, they are oligopolies. Oligopoly arises when a small number of large firms have all or nearly of the sales in an industry. Examples of oligopoly grow and include the auto industry, cable television, and commercial air travel. Oligopolistic firms are similar cats in a bag. They can either scratch each other to pieces or cuddle up and go comfortable with 1 another. If oligopolists compete hard, they may finish upwards acting very much like perfect competitors, driving downwardly costs and leading to nil profits for all. If oligopolists collude with each other, they may effectively act like a monopoly and succeed in pushing up prices and earning consistently high levels of profit. Oligopolies are typically characterized by mutual interdependence where various decisions such as output, price, advertising, and then on, depend on the decisions of the other firm(s). Analyzing the choices of oligopolistic firms about pricing and quantity produced involves considering the pros and cons of competition versus collusion at a given point in time.

Why Do Oligopolies Be?

A combination of the barriers to entry that create monopolies and the product differentiation that characterizes monopolistic competition can create the setting for an oligopoly. For example, when a authorities grants a patent for an invention to one firm, it may create a monopoly. When the government grants patents to, for case, three unlike pharmaceutical companies that each has its own drug for reducing high blood pressure level, those three firms may become an oligopoly.

Similarly, a natural monopoly will ascend when the quantity demanded in a market is only big plenty for a single firm to operate at the minimum of the long-run average price bend. In such a setting, the market has room for only ane firm, because no smaller firm tin operate at a depression enough average cost to compete, and no larger firm could sell what it produced given the quantity demanded in the market.

Quantity demanded in the market may besides be two or iii times the quantity needed to produce at the minimum of the average cost curve—which means that the market place would have room for only two or three oligopoly firms (and they need not produce differentiated products). Again, smaller firms would have college average costs and be unable to compete, while additional large firms would produce such a high quantity that they would not be able to sell information technology at a assisting price. This combination of economies of scale and market need creates the barrier to entry, which led to the Boeing-Airbus oligopoly for big passenger aircraft.

The product differentiation at the center of monopolistic competition can as well play a role in creating oligopoly. For instance, firms may demand to accomplish a certain minimum size before they are able to spend plenty on advertisement and marketing to create a recognizable brand name. The problem in competing with, say, Coca-Cola or Pepsi is non that producing fizzy drinks is technologically hard, but rather that creating a brand proper name and marketing effort to equal Coke or Pepsi is an enormous task.

Collusion or Competition?

When oligopoly firms in a sure marketplace decide what quantity to produce and what cost to charge, they face a temptation to act every bit if they were a monopoly. By interim together, oligopolistic firms can hold downwardly industry output, charge a higher price, and divide up the turn a profit amidst themselves. When firms human action together in this mode to reduce output and go along prices high, it is chosen collusion. A group of firms that have a formal agreement to collude to produce the monopoly output and sell at the monopoly price is called a cartel. Meet the following Clear It Up feature for a more in-depth analysis of the difference between the 2.

Bunco versus cartels: How tin can I tell which is which?

In the United States, as well as many other countries, it is illegal for firms to collude since collusion is anti-competitive behavior, which is a violation of antitrust law. Both the Antitrust Division of the Justice Section and the Federal Merchandise Committee have responsibilities for preventing collusion in the United states.

The problem of enforcement is finding hard evidence of collusion. Cartels are formal agreements to collude. Because cartel agreements provide evidence of bunco, they are rare in the United States. Instead, virtually bunco is tacit, where firms implicitly accomplish an understanding that competition is bad for profits.

The desire of businesses to avert competing then that they can instead raise the prices that they accuse and earn higher profits has been well understood by economists. Adam Smith wrote in Wealth of Nations in 1776: "People of the aforementioned merchandise seldom see together, even for merriment and diversion, merely the chat ends in a conspiracy confronting the public, or in some contrivance to raise prices."

Even when oligopolists recognize that they would benefit as a group by acting like a monopoly, each private oligopoly faces a individual temptation to produce just a slightly college quantity and earn slightly higher profit—while still counting on the other oligopolists to agree down their production and keep prices high. If at to the lowest degree some oligopolists requite in to this temptation and beginning producing more, and so the market price will fall. Indeed, a modest handful of oligopoly firms may finish upward competing and then fiercely that they all end up earning naught economic profits—as if they were perfect competitors.

The Prisoner's Dilemma

Because of the complication of oligopoly, which is the result of common interdependence among firms, in that location is no single, mostly-accepted theory of how oligopolies carry, in the same way that we accept theories for all the other marketplace structures. Instead, economists utilise game theory, a co-operative of mathematics that analyzes situations in which players must make decisions and then receive payoffs based on what other players decide to do. Game theory has institute widespread applications in the social sciences, as well as in business organization, law, and armed services strategy.

The prisoner'south dilemma is a scenario in which the gains from cooperation are larger than the rewards from pursuing cocky-interest. It applies well to oligopoly. The story backside the prisoner'due south dilemma goes like this:

Two co-conspiratorial criminals are arrested. When they are taken to the constabulary station, they turn down to say anything and are put in split up interrogation rooms. Eventually, a police force officeholder enters the room where Prisoner A is being held and says: "You know what? Your partner in the other room is confessing. And so your partner is going to go a light prison judgement of just one twelvemonth, and because you're remaining silent, the estimate is going to stick yous with eight years in prison house. Why don't you lot become smart? If you confess, too, we'll cutting your jail time down to five years, and your partner volition get 5 years, also." Over in the next room, some other police officer is giving exactly the aforementioned spoken language to Prisoner B. What the police officers exercise not say is that if both prisoners remain silent, the evidence against them is not specially strong, and the prisoners volition end up with but two years in jail each.

The game theory state of affairs facing the two prisoners is shown in Table 3. To sympathise the dilemma, first consider the choices from Prisoner A'due south point of view. If A believes that B will confess, then A ought to confess, too, so as to not go stuck with the eight years in prison house. Just if A believes that B will not confess, then A volition be tempted to act selfishly and confess, and so every bit to serve only 1 year. The key point is that A has an incentive to confess regardless of what choice B makes! B faces the same prepare of choices, and thus will take an incentive to confess regardless of what option A makes. Confess is considered the dominant strategy or the strategy an individual (or firm) will pursue regardless of the other private's (or firm'due south) decision. The upshot is that if prisoners pursue their own self-interest, both are likely to confess, and end upwards doing a total of 10 years of jail time between them.

| Prisoner B | |||

| Remain Silent (cooperate with other prisoner) | Confess (do not cooperate with other prisoner) | ||

| Prisoner A | Remain Silent (cooperate with other prisoner) | A gets two years, B gets 2 years | A gets 8 years, B gets 1 yr |

| Confess (practice not cooperate with other prisoner) | A gets 1 year, B gets 8 years | A gets 5 years B gets 5 years | |

| Tabular array three. The Prisoner's Dilemma Problem | |||

The game is chosen a dilemma because if the 2 prisoners had cooperated by both remaining silent, they would only have had to serve a total of four years of jail time between them. If the 2 prisoners can work out some way of cooperating and so that neither 1 will confess, they volition both exist ameliorate off than if they each follow their ain individual self-interest, which in this case leads straight into longer jail terms.

The Oligopoly Version of the Prisoner's Dilemma

The members of an oligopoly tin confront a prisoner's dilemma, besides. If each of the oligopolists cooperates in holding downward output, so loftier monopoly profits are possible. Each oligopolist, withal, must worry that while it is holding down output, other firms are taking reward of the high price by raising output and earning higher profits. Table 4 shows the prisoner's dilemma for a two-firm oligopoly—known as a duopoly. If Firms A and B both agree to hold downwards output, they are acting together as a monopoly and will each earn $1,000 in profits. Notwithstanding, both firms' dominant strategy is to increase output, in which case each will earn $400 in profits.

| Firm B | |||

| Concord Down Output (cooperate with other house) | Increase Output (do non cooperate with other firm) | ||

| House A | Concur Downwardly Output (cooperate with other firm) | A gets $ane,000, B gets $1,000 | A gets $200, B gets $ane,500 |

| Increase Output (do non cooperate with other firm) | A gets $1,500, B gets $200 | A gets $400, B gets $400 | |

| Table 4. A Prisoner's Dilemma for Oligopolists | |||

Tin can the ii firms trust each other? Consider the state of affairs of Firm A:

- If A thinks that B will crook on their agreement and increment output, then A will increase output, also, considering for A the turn a profit of $400 when both firms increase output (the bottom correct-manus choice in Table 4) is better than a profit of only $200 if A keeps output low and B raises output (the upper right-hand selection in the tabular array).

- If A thinks that B volition cooperate by holding downwardly output, then A may seize the opportunity to earn higher profits by raising output. Later on all, if B is going to hold down output, then A can earn $ane,500 in profits by expanding output (the bottom left-manus choice in the tabular array) compared with only $one,000 past property down output as well (the upper left-mitt selection in the tabular array).

Thus, firm A volition reason that it makes sense to expand output if B holds downwardly output and that it likewise makes sense to expand output if B raises output. Again, B faces a parallel fix of decisions.

The result of this prisoner's dilemma is frequently that even though A and B could brand the highest combined profits by cooperating in producing a lower level of output and acting similar a monopolist, the two firms may well stop up in a situation where they each increase output and earn only $400 each in profits. The following Articulate It Upwards feature discusses one cartel scandal in detail.

What is the Lysine cartel?

Lysine, a $600 1000000-a-year industry, is an amino acid used by farmers as a feed condiment to ensure the proper growth of swine and poultry. The main U.S. producer of lysine is Archer Daniels Midland (ADM), merely several other big European and Japanese firms are also in this market. For a fourth dimension in the first half of the 1990s, the world'due south major lysine producers met together in hotel briefing rooms and decided exactly how much each firm would sell and what it would charge. The U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), withal, had learned of the cartel and placed wire taps on a number of their telephone calls and meetings.

From FBI surveillance tapes, following is a comment that Terry Wilson, president of the corn processing partitioning at ADM, made to the other lysine producers at a 1994 meeting in Mona, Hawaii:

I wanna get back and I wanna say something very simple. If we're going to trust each other, okay, and if I'thousand assured that I'g gonna get 67,000 tons by the twelvemonth'southward end, we're gonna sell information technology at the prices nosotros agreed to . . . The only thing we need to talk about at that place because we are gonna get manipulated past these [expletive] buyers—they tin can be smarter than united states if we let them be smarter. . . . They [the customers] are not your friend. They are not my friend. And we gotta have 'em, simply they are not my friends. You are my friend. I wanna be closer to you than I am to whatever customer. Cause you lot can make us … money. … And all I wanna tell you lot over again is let's—let's put the prices on the board. Let's all hold that's what nosotros're gonna do and then walk out of hither and practice it.

The toll of lysine doubled while the cartel was in event. Confronted by the FBI tapes, Archer Daniels Midland pled guilty in 1996 and paid a fine of $100 one thousand thousand. A number of pinnacle executives, both at ADM and other firms, after paid fines of up to $350,000 and were sentenced to 24–30 months in prison house.

In another one of the FBI recordings, the president of Archer Daniels Midland told an executive from another competing firm that ADM had a slogan that, in his words, had "penetrated the whole company." The company president stated the slogan this way: "Our competitors are our friends. Our customers are the enemy." That slogan could stand up as the motto of cartels everywhere.

How to Enforce Cooperation

How can parties who find themselves in a prisoner's dilemma state of affairs avoid the undesired outcome and cooperate with each other? The way out of a prisoner'south dilemma is to detect a mode to penalize those who practice not cooperate.

Perhaps the easiest approach for colluding oligopolists, as you lot might imagine, would exist to sign a contract with each other that they will hold output low and continue prices high. If a grouping of U.South. companies signed such a contract, nevertheless, it would be illegal. Certain international organizations, like the nations that are members of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), have signed international agreements to act like a monopoly, hold down output, and keep prices high so that all of the countries tin make high profits from oil exports. Such agreements, however, considering they fall in a gray area of international police, are not legally enforceable. If Nigeria, for example, decides to start cutting prices and selling more than oil, Kingdom of saudi arabia cannot sue Nigeria in court and force it to terminate.

Visit the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries website and larn more about its history and how it defines itself.

Because oligopolists cannot sign a legally enforceable contract to deed like a monopoly, the firms may instead go on close tabs on what other firms are producing and charging. Alternatively, oligopolists may choose to act in a way that generates pressure on each business firm to stick to its agreed quantity of output.

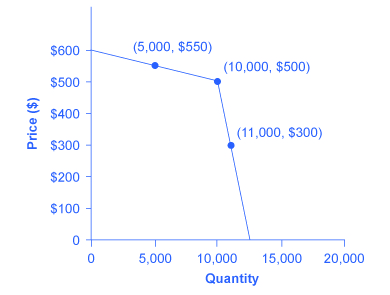

1 case of the pressure these firms can exert on one another is the kinked demand curve, in which competing oligopoly firms commit to friction match price cuts, but not cost increases. This situation is shown in Figure 1. Say that an oligopoly airline has agreed with the residuum of a dare to provide a quantity of 10,000 seats on the New York to Los Angeles route, at a toll of $500. This choice defines the kink in the firm'southward perceived need curve. The reason that the firm faces a kink in its demand curve is considering of how the other oligopolists react to changes in the firm'south price. If the oligopoly decides to produce more and cutting its price, the other members of the cartel will immediately match whatsoever price cuts—and therefore, a lower price brings very niggling increment in quantity sold.

If one firm cuts its price to $300, information technology will be able to sell only eleven,000 seats. However, if the airline seeks to heighten prices, the other oligopolists will not raise their prices, and so the house that raised prices volition lose a considerable share of sales. For example, if the house raises its price to $550, its sales drop to 5,000 seats sold. Thus, if oligopolists always match toll cuts by other firms in the cartel, but exercise not match price increases, so none of the oligopolists will have a strong incentive to change prices, since the potential gains are minimal. This strategy tin can work similar a silent form of cooperation, in which the cartel successfully manages to hold downwardly output, increase price, and share a monopoly level of profits even without any legally enforceable agreement.

Many real-world oligopolies, prodded by economic changes, legal and political pressures, and the egos of their top executives, go through episodes of cooperation and competition. If oligopolies could sustain cooperation with each other on output and pricing, they could earn profits as if they were a single monopoly. However, each house in an oligopoly has an incentive to produce more than and grab a bigger share of the overall marketplace; when firms start behaving in this fashion, the market place outcome in terms of prices and quantity tin can be similar to that of a highly competitive market.

Tradeoffs of Imperfect Competition

Monopolistic competition is probably the single nigh mutual market structure in the U.South. economy. It provides powerful incentives for innovation, as firms seek to earn profits in the short run, while entry assures that firms do non earn economic profits in the long run. All the same, monopolistically competitive firms do not produce at the everyman betoken on their average cost curves. In addition, the endless search to impress consumers through product differentiation may lead to excessive social expenses on advert and marketing.

Oligopoly is probably the second nearly mutual marketplace structure. When oligopolies result from patented innovations or from taking advantage of economies of scale to produce at low boilerplate cost, they may provide considerable benefit to consumers. Oligopolies are often buffeted by significant barriers to entry, which enable the oligopolists to earn sustained profits over long periods of time. Oligopolists besides practice not typically produce at the minimum of their average cost curves. When they lack vibrant contest, they may lack incentives to provide innovative products and high-quality service.

The task of public policy with regard to contest is to sort through these multiple realities, attempting to encourage behavior that is beneficial to the broader society and to discourage behavior that but adds to the profits of a few large companies, with no respective benefit to consumers. Monopoly and Antitrust Policy discusses the delicate judgments that become into this task.

The Temptation to Defy the Police force

Oligopolistic firms have been called "cats in a bag," as this chapter mentioned. The French detergent makers chose to "cozy upwardly" with each other. The upshot? An uneasy and tenuous relationship. When the Wall Street Periodical reported on the matter, it wrote: "Co-ordinate to a argument a Henkel manager made to the [French anti-trust] committee, the detergent makers wanted 'to limit the intensity of the competition between them and clean up the market.' Yet, past the early on 1990s, a cost state of war had broken out among them." During the soap executives' meetings, which sometimes lasted more iv hours, complex pricing structures were established. "One [soap] executive recalled 'chaotic' meetings as each side tried to work out how the other had bent the rules." Like many cartels, the soap cartel disintegrated due to the very strong temptation for each fellow member to maximize its own individual profits.

How did this lather opera stop? Afterwards an investigation, French antitrust government fined Colgate-Palmolive, Henkel, and Proctor & Gamble a total of €361 million ($484 million). A like fate befell the icemakers. Bagged water ice is a commodity, a perfect substitute, mostly sold in vii- or 22-pound bags. No i cares what label is on the bag. By agreeing to cleave up the water ice marketplace, control broad geographic swaths of territory, and set prices, the icemakers moved from perfect competition to a monopoly model. After the agreements, each firm was the sole supplier of bagged ice to a region; there were profits in both the long run and the short run. According to the courts: "These companies illegally conspired to manipulate the market." Fines totaled about $600,000—a steep fine considering a bag of ice sells for nether $iii in most parts of the United States.

Even though it is illegal in many parts of the globe for firms to set up prices and cleave up a market, the temptation to earn higher profits makes it extremely tempting to defy the law.

Cardinal Concepts and Summary

An oligopoly is a state of affairs where a few firms sell nearly or all of the goods in a market. Oligopolists earn their highest profits if they can ring together equally a dare and act similar a monopolist by reducing output and raising price. Since each fellow member of the oligopoly can do good individually from expanding output, such collusion often breaks downwards—especially since explicit collusion is illegal.

The prisoner's dilemma is an example of game theory. It shows how, in certain situations, all sides tin benefit from cooperative behavior rather than self-interested behavior. However, the challenge for the parties is to notice ways to encourage cooperative behavior.

Self-Check Questions

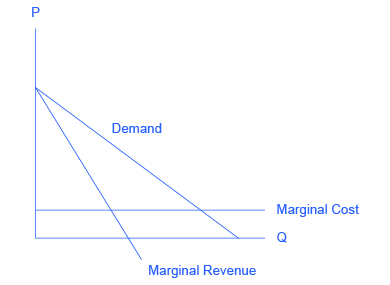

- Consider the curve shown in Figure two, which shows the market place demand, marginal toll, and marginal revenue curve for firms in an oligopolistic industry. In this example, we assume firms have zero stock-still costs.

Figure 2. - Suppose the firms collude to class a cartel. What price will the dare accuse? What quantity will the cartel supply? How much profit will the cartel earn?

- Suppose at present that the cartel breaks upwards and the oligopolistic firms compete as vigorously every bit possible past cutting the cost and increasing sales. What will the industry quantity and price be? What will the collective profits exist of all firms in the industry?

- Compare the equilibrium price, quantity, and profit for the cartel and cutthroat contest outcomes.

- Sometimes oligopolies in the aforementioned industry are very different in size. Suppose we accept a duopoly where one firm (Firm A) is large and the other firm (Firm B) is small, as shown in the prisoner's dilemma box in Table 5.

Business firm B colludes with Firm A Firm B cheats by selling more output Firm A colludes with Firm B A gets $one,000, B gets $100 A gets $800, B gets $200 Firm A cheats past selling more output A gets $1,050, B gets $50 A gets $500, B gets $20 Table 5. Assuming that the payoffs are known to both firms, what is the likely outcome in this case?

Review Questions

- Will the firms in an oligopoly human activity more like a monopoly or more like competitors? Briefly explicate.

- Does each individual in a prisoner'southward dilemma benefit more than from cooperation or from pursuing self-interest? Explain briefly.

- What stops oligopolists from interim together equally a monopolist and earning the highest possible level of profits?

Critical Thinking Questions

- Would y'all expect the kinked demand bend to be more farthermost (like a correct bending) or less farthermost (like a normal demand bend) if each house in the cartel produces a near-identical production like OPEC and petroleum? What if each firm produces a somewhat dissimilar product? Explicate your reasoning.

- When OPEC raised the price of oil dramatically in the mid-1970s, experts said it was unlikely that the cartel could stay together over the long term—that the incentives for individual members to cheat would get too potent. More than than forty years later, OPEC still exists. Why do y'all think OPEC has been able to beat out the odds and proceed to collude? Hint: You lot may wish to consider non-economical reasons.

Problems

- Mary and Raj are the only two growers who provide organically grown corn to a local grocery store. They know that if they cooperated and produced less corn, they could enhance the price of the corn. If they work independently, they volition each earn $100. If they make up one's mind to work together and both lower their output, they can each earn $150. If one person lowers output and the other does not, the person who lowers output will earn $0 and the other person will capture the entire market and will earn $200. Table 6 represents the choices bachelor to Mary and Raj. What is the best choice for Raj if he is certain that Mary volition cooperate? If Mary thinks Raj volition crook, what should Mary exercise and why? What is the prisoner's dilemma effect? What is the preferred selection if they could ensure cooperation? A = Work independently; B = Cooperate and Lower Output. (Each results entry lists Raj'south earnings get-go, and Mary's earnings second.)

- Jane and Bill are apprehended for a bank robbery. They are taken into separate rooms and questioned past the police about their involvement in the crime. The police tell them each that if they confess and turn the other person in, they will receive a lighter sentence. If they both confess, they will be each exist sentenced to 30 years. If neither confesses, they will each receive a 20-year sentence. If but one confesses, the confessor will receive fifteen years and the i who stayed silent will receive 35 years. Table 7 beneath represents the choices bachelor to Jane and Pecker. If Jane trusts Pecker to stay silent, what should she practise? If Jane thinks that Pecker volition confess, what should she practice? Does Jane have a dominant strategy? Does Bill accept a dominant strategy? A = Confess; B = Stay Silent. (Each results entry lists Jane's sentence commencement (in years), and Bill's sentence second.)

Jane A B Bill A (thirty, 30) (15, 35) B (35, xv) (twenty, 20) Table 7.

References

The The states Department of Justice. "Antitrust Division." Accessed Oct 17, 2013. http://www.justice.gov/atr/.

eMarketer.com. 2014. "Total US Advertisement Spending to See Largest Increase Since 2004: Mobile ad leads growth; will surpass radio, magazines and newspapers this twelvemonth. Accessed March 12, 2015. http://www.emarketer.com/Commodity/Total-The states-Ad-Spending-See-Largest-Increase-Since-2004/1010982.

Federal Trade Commission. "About the Federal Trade Commission." Accessed October 17, 2013. http://www.ftc.gov/ftc/about.shtm.

Glossary

- cartel

- a group of firms that collude to produce the monopoly output and sell at the monopoly price

- collusion

- when firms act together to reduce output and keep prices high

- duopoly

- an oligopoly with only 2 firms

- game theory

- a branch of mathematics often used by economists that analyzes situations in which players must make decisions and then receive payoffs based on what decisions the other players brand

- kinked demand curve

- a perceived demand bend that arises when competing oligopoly firms commit to match price cuts, but not cost increases

- prisoner's dilemma

- a game in which the gains from cooperation are larger than the rewards from pursuing self-interest

Solutions

Answers to Cocky-Bank check Questions

-

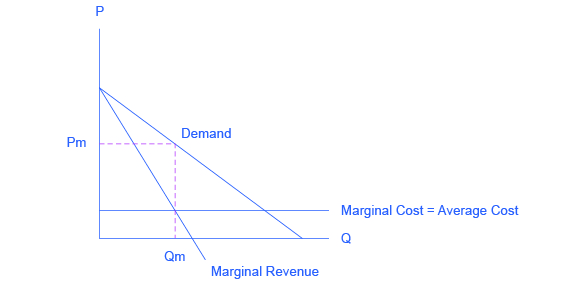

- If the firms grade a dare, they volition deed like a monopoly, choosing the quantity of output where MR = MC. Drawing a line from the monopoly quantity upwards to the demand bend shows the monopoly price. Bold that stock-still costs are aught, and with an understanding of cost and turn a profit, we can infer that when the marginal cost bend is horizontal, boilerplate cost is the same as marginal toll. Thus, the cartel will earn positive economical profits equal to the surface area of the rectangle, with a base of operations equal to the monopoly quantity and a pinnacle equal to the divergence between cost (on the demand above the monopoly quantity) and average toll, equally shown in the post-obit figure.

Figure 3. - The firms will expand output and cut price as long as there are profits remaining. The long-run equilibrium will occur at the betoken where average price equals demand. As a result, the oligopoly volition earn zip economic profits due to "cutthroat contest," equally shown in the side by side effigy.

Effigy 4. - Pc > Pcc. Qc < Qcc. Profit for the dare is positive and large. Turn a profit for cutthroat competition is zero.

- If the firms grade a dare, they volition deed like a monopoly, choosing the quantity of output where MR = MC. Drawing a line from the monopoly quantity upwards to the demand bend shows the monopoly price. Bold that stock-still costs are aught, and with an understanding of cost and turn a profit, we can infer that when the marginal cost bend is horizontal, boilerplate cost is the same as marginal toll. Thus, the cartel will earn positive economical profits equal to the surface area of the rectangle, with a base of operations equal to the monopoly quantity and a pinnacle equal to the divergence between cost (on the demand above the monopoly quantity) and average toll, equally shown in the post-obit figure.

- Business firm B reasons that if it cheats and Firm A does not detect, information technology will double its money. Since Business firm A's profits will refuse substantially, however, it is probable that Business firm A volition notice and if and so, House A will cheat also, with the effect that Firm B volition lose 90% of what information technology gained past adulterous. Firm A volition reason that Firm B is unlikely to risk cheating. If neither firm cheats, Business firm A earns $1000. If Firm A cheats, assuming Firm B does not cheat, A can boost its profits only a little, since House B is so pocket-size. If both firms cheat, so Firm A loses at least 50% of what it could have earned. The possibility of a small proceeds ($50) is probably non enough to induce Business firm A to cheat, and so in this instance information technology is probable that both firms will collude.

Source: https://opentextbc.ca/principlesofeconomics/chapter/10-2-oligopoly/

0 Response to "Consider Exercise 2 Again. Assume That the Firms Form a Cartel"

Post a Comment